It’s not easy to construct an E-911 system for a single building, and the issues multiply when trying to cover an office complex or educational campus. Then multiply those challenges by 100 or more to get an idea of what it takes to deploy a system across an entire state.

“We have dozens of situations and use cases we need to address,” said Thomas Dietrich, telecommunications operations manager for the State of Washington’s Department of Transportation. “But regardless of location, our goal is to support the first responders and help them address emergencies that occur on our transportation network.”

Dietrich presented a seminar at Avaya ENGAGE 2020, “911 Solutions from the Perspective of a Transportation and Public Safety,” that was reprised for the IAUG WIRED virtual conference in May. Kevin Kito, 911 Secure LLC, introduced Dietrich at the session.

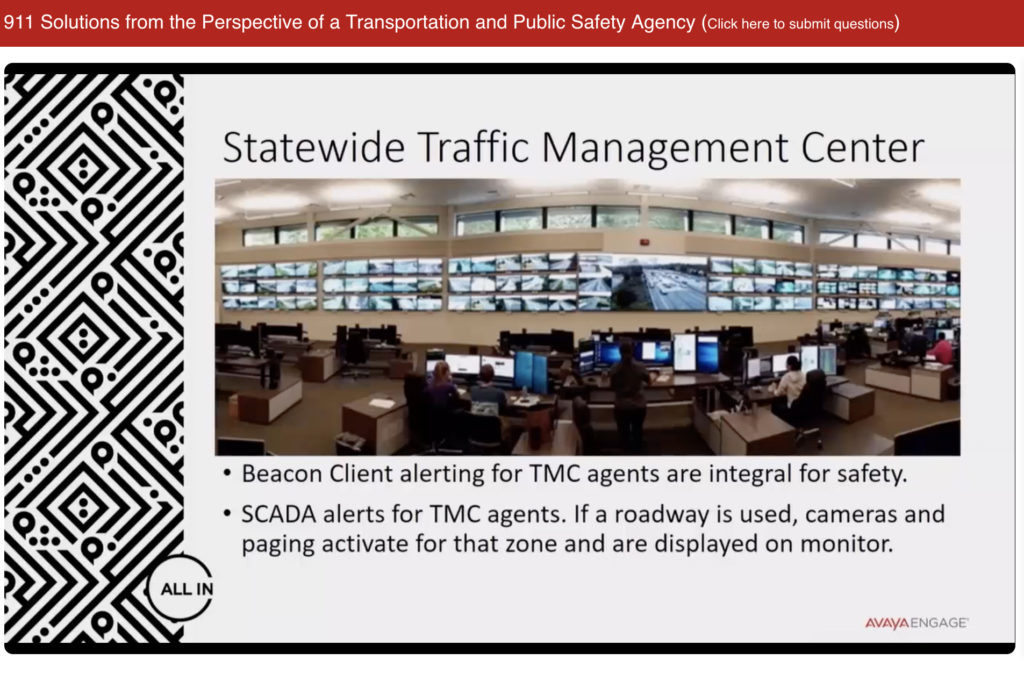

With their statewide responsibilities, Dietrich and his team monitor emergency phones and beacons from six traffic management centers (TMCs) including the main facility in the Seattle area. Notifications are routed to each TMC based on their regional coverage areas. The statewide 911 infrastructure covers empty desert highways, winding mountains roads, bridges, tunnels and the crowded roads throughout the Seattle-Tacoma metropolitan area. In addition, the team is responsible for 911 calls on ferries transporting passengers to the islands in Puget Sound and adjacent waters north to British Columbia.

The 911 network includes SIP phones on roadways, as well as communication bunkers with hard-wire connectivity in areas like mountain passes without cell phone connectivity. “We can define a location and work with the local PSAP to define how to get local responders to that site,” he said. “We also need to ensure connectivity for our response crews and maintenance vehicles heading to the same location.”

When an emergency call or alert comes in, the call goes to the person with the right skills to handle the issue, said Dietrich. “That staffer can turn on a camera in many locations to see what’s going on and determine the proper traffic response, while guiding first responders to the emergency location.” For example, the operations team monitors a floating bridge that carries Interstate 90 across Lake Washington and then into a tunnel east of Seattle. When an alert occurs n the tunnel, the team can turn up the HVAC system to evacuate any smoke or fumes.

The operations team also monitors ferries traveling the state’s coastal waters. “We want to know the vessel’s location,” Dietrich said. “If it’s about to come into port on an island or here in Seattle, we can notify the terminal so help is available on arrival.” The team also gets calls for emergency assistance from the ferry terminals. “Many times a ticket seller might call to let us know that a passenger has seen an accident or breakdown on the road coming into the terminal,” he added.

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, Dietrich had encouraged team members to work from home, with hoteling/desk swapping arrangements in the office. Staffers can log on and off with a SIP phone and use the Sentry Gatekeeper application for location services in case of an on-site emergency.

Asked for suggestions for implementing a 911 service with multiple use cases, Dietrich said to look for simplicity. “You want a set-it and forget-it application, along with clear maintenance plan,” he said. “Look for a single vendor solution and stay current with all security updates. Remember that an emergency situation can occur at any time, so run practice drills and be prepared for the unexpected as well.”

Like!! Thank you for publishing this awesome article.